It's me, hi, I'm the problem, it's me

At tea time, everybody agrees

I'll stare directly at the sun but never in the mirror

It must be exhausting always rooting for the anti-heroAnti-Hero, Taylor Swift

This is a luddite’s opinion, so take it from whence it comes, but I have been staggered at how panicked the world is about AI and how it’s going to steal our very humanity from us by writing terrible books and creating lame art and putting coders out of jobs cos now the machines can do it. Sure, there are arguments to be had there, but they don’t really interest me. People who think critically and strategically have always been able to harness the latest technology as a tool as opposed to seeing it as an existential threat. The real problem, as it always has been, is inequality, and the ability of capitalism to exacerbate inequality when technological advances should mean the opposite[i]. So, as ever, it is low-level workers who will bear the brunt of this technological evolution in terms of livelihood. But that is not my main concern, here, today.

Rather, what I have been amazed by, and what I want to draw your attention to, is how popular discourse on AI hardly ever includes information of what seems to be the clear ecological crisis it is pointing to. As well as being a luddite, I am, paradoxically, equally unschooled in the energy crisis, climate change, and ecological disaster. Beyond the headlines, all I can ascertain is that we are in trouble.

But even with such scant knowledge on tech and the environment I still know to ask: but where are the physical machines running these AI models and how much power do they use? Like, where are the servers? And who is paying for them? And how are they paying for them? Cost is not only monetary.

In an article on The Obscene Energy Demands of AI from the New Yorker in March this year, Elizabeth Kolbert asks, “How can the world reach net zero if it keeps inventing new ways to consume energy?”

She writes that, ‘In 2016, Alex de Vries read somewhere that a single bitcoin transaction consumes as much energy as the average American household uses in a day.’ Spurred on by his curiosity as to why no-one was talking about this, he went on to ‘put together what he called the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, and posted it on Digiconomist. According to the index’s latest figures, bitcoin mining now consumes a hundred and forty-five billion kilowatt-hours of electricity per year, which is more than is used by the entire nation of the Netherlands, and producing that electricity results in eighty-one million tons of CO2, which is more than the annual emissions of a nation like Morocco.

‘De Vries subsequently began to track the electronic waste produced by bitcoin mining—an iPhone’s worth for every transaction—and its water use—which is something like two trillion litres per year. (The water goes toward cooling the servers used in mining, and the e-waste is produced by servers that have become out of date.)’

He has continued working in this space and is now focused on educating people on AI’s energy consumption. De Vries calculated that ‘if Google were to integrate generative A.I. into every search, its electricity use would rise to something like twenty-nine billion kilowatt-hours per year. This is more than is consumed by many countries, including Kenya, Guatemala, and Croatia.’

‘ “There’s a fundamental mismatch between this technology and environmental sustainability,” de Vries said. Recently, the world’s most prominent A.I. cheerleader, Sam Altman, the C.E.O. of OpenAI, voiced similar concerns, albeit with a different spin. “I think we still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology,” Altman said at a public appearance in Davos. He didn’t see how these needs could be met, he went on, “without a breakthrough.” He added, “We need fusion or we need, like, radically cheaper solar plus storage, or something, at massive scale—like, a scale that no one is really planning for.”’

Kolbert notes that ‘the kind of machine learning that produced ChatGPT relies on models that process fantastic amounts of information, and every bit of processing takes energy. When ChatGPT spits out information (or writes someone’s high-school essay), that, too, requires a lot of processing. It’s been estimated that ChatGPT is responding to something like two hundred million requests per day, and, in so doing, is consuming more than half a million kilowatt-hours of electricity. (For comparison’s sake, the average U.S. household consumes twenty-nine kilowatt-hours a day.)’

It is not only electricity consumption that is concerning. In an article by Kate Crawford in Nature, she writes that, ‘Generative AI systems need enormous amounts of fresh water to cool their processors and generate electricity. In West Des Moines, Iowa, a giant data-centre cluster serves OpenAI’s most advanced model, GPT-4. A lawsuit by local residents revealed that in July 2022, the month before OpenAI finished training the model, the cluster used about 6% of the district’s water. As Google and Microsoft prepared their Bard and Bing large language models, both had major spikes in water use — increases of 20% and 34%, respectively, in one year, according to the companies’ environmental reports. One preprint1 suggests that, globally, the demand for water for AI could be half that of the United Kingdom by 2027.’

Crawford concludes that, ‘The full planetary costs of generative AI are closely guarded corporate secrets’.

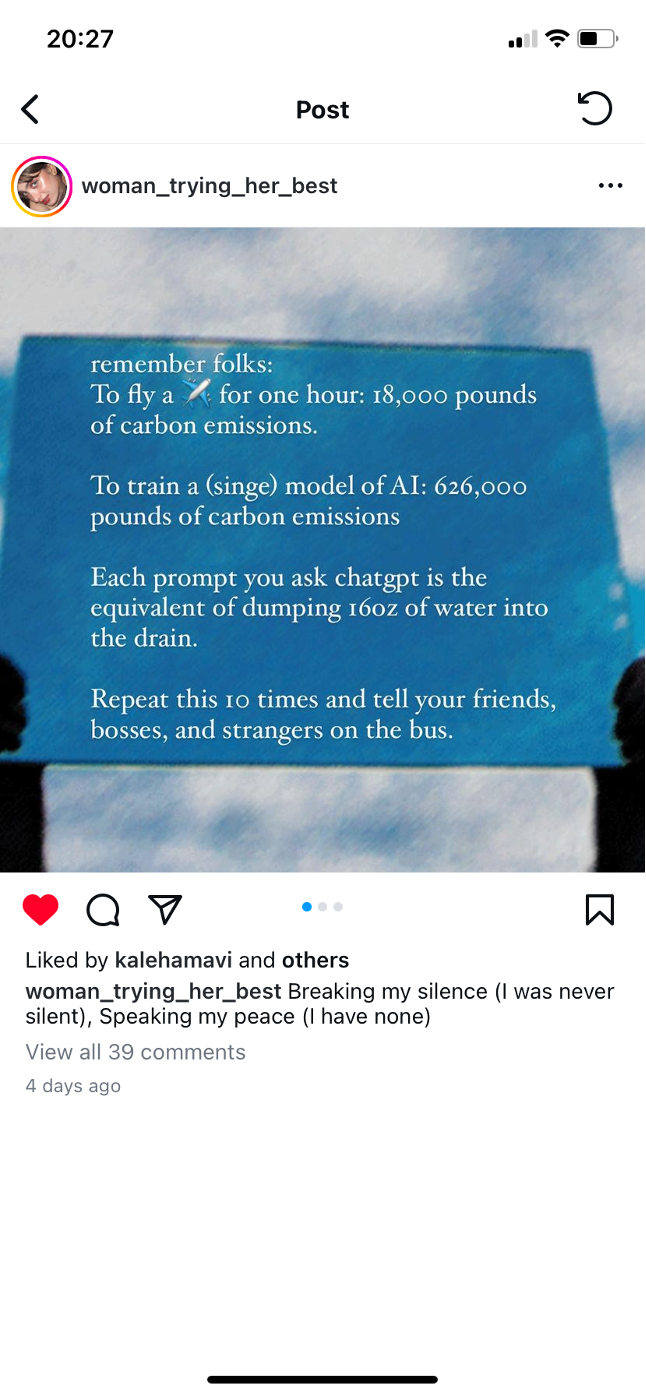

I think we are compelled to bring these secrets out into the open and start talking about them whenever the inevitable AI conversation comes up. Now you know as much as I do. Below are some links to further reading if you would like to learn more. And if you come across any helpful resources on this topic, please send them to me. Thanks!

But if spreading the gospel on the socials is more your thing, here is some content for you to share.

Further reading:

https://hbr.org/2024/07/the-uneven-distribution-of-ais-environmental-impacts

https://digiconomist.net/powering-ai-could-use-as-much-electricity-as-a-small-country/

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00478-x

[i] “The uneven distribution of AI’s environmental impacts often remains hidden from public view and can potentially create unforeseen socioeconomic ramifications. We aim to raise awareness within the business community and among the general public regarding AI’s emerging environmental inequity. As we strive to develop environmentally responsible AI, we must not solely concentrate on easily measurable sustainability metrics, such as the total carbon emission and water consumption, while overlooking equity in the process. AI’s environmental impacts must resonate with the priorities and interests of local regions.” https://hbr.org/2024/07/the-uneven-distribution-of-ais-environmental-impacts